It is well known in all programming languages the floating point math loses some accuracy. Therefore we have something like the following statement

1

0.1 + 0.2 != 0.3

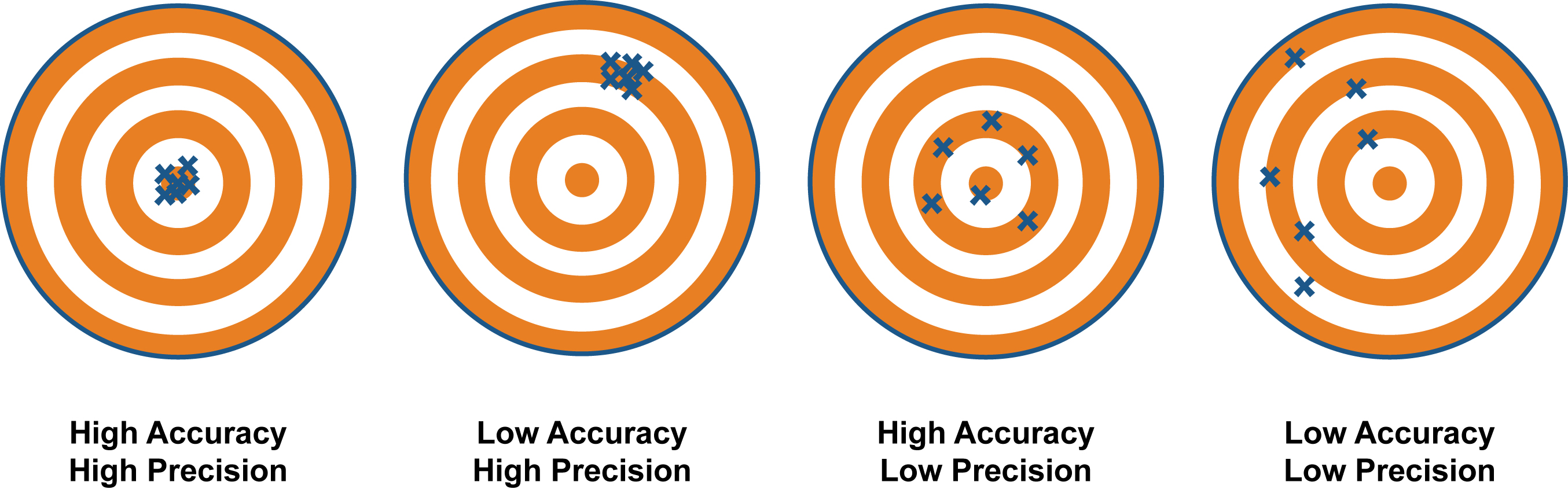

This is explained in detail in here, but basically, is because some fractional numbers aren’t well represented on binary, and the carryover loses accuracy, but it keeps precise.

There are several ways to mitigate this effect, the most known use double numbers or big decimal representations, the problem with those is the operations tend to use more computing resources, especially with BigNumbers, that usually are objects with large strings and complicated math behind.

Money (high accuracy, high precision)

Let’s assume we are representing money if we choose to store float values in our database, in that case, our business will lose money. If we use a double precision data type we gain accuracy, with a little price of resources but is not enough, our company cannot lose any cent. Using BigData it will solve the problem, but to perform calculations, more computing resources are required. The best solution for this case is by using cents and represent everything on integers(computers work better with integers), and we will never have half cents in any currency.

Metrics and Graphics (high precision with less accuracy or vice verse)

In statistics or graphics, having a 100% accuracy and precision do not make any difference. Because from the human perspective is the same to have 40.54 to 40.5349 and in graphics, those small differences aren´t perceptible. As long as we keep our metrics close to the reality and humanly readable, we can use float values, without hesitating.

Sensors and Space (very high accuracy, very high precision)

As in an article recent published here, we can see how the NASA it only uses 14 decimals of Pi to send a man to the moon. That is very impressive, although some developers think that, having more than 14 decimals are not enough for the calculations, especially if our application gather information from sensors. But we still need high accuracy and precision, the question is, how much?

Benchmark data preparation

I generate an SQLite database with around 1.5M data points and copy the values in four different data types:

- Integer: using the four first decimals

- Integer: using the eight first decimals

- Real: using the float value

- Text: as it is from the source to be parsed within a BigDecimal

Benchmark design

The simplest operation from a computer is the addition, so for each data type, it will be added the entire data points and compared with the big decimal value, to estimate the error. For the integer values, after the addition, a division it’s needed to restore the float type and get the closest approximation, to the real value.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

require 'sqlite3'

require 'bigdecimal'

require 'benchmark/ips'

DB = SQLite3::Database.new 'data.db'

def sum_int

rows = DB.execute("SELECT value_int FROM points")

rows.flatten.map(&:to_i).inject(:+).to_i / 10_000.0

end

def sum_big_int

rows = DB.execute("SELECT value_big_int FROM points")

rows.flatten.map(&:to_i).inject(:+).to_i / 100_000_000.0

end

def sum_real

rows = DB.execute("SELECT value_real FROM points")

rows.flatten.map(&:to_f).inject(:+)

end

def sum_txt

rows = DB.execute("SELECT value_txt FROM points")

rows.flatten.map{ |x| BigDecimal.new(x) }.inject(:+)

end

real_value = sum_txt.to_f

puts "SUM error = #{(real_value - real_value) / real_value}, text = #{sum_txt.to_f}"

puts "SUM error = #{(real_value - sum_real) / real_value}, real = #{sum_real}"

puts "SUM error = #{(real_value - sum_big_int) / real_value}, bint = #{sum_big_int}"

puts "SUM error = #{(real_value - sum_int) / real_value}, int = #{sum_int}"

Benchmark.ips do |x|

x.config(time: 10, warmup: 2)

x.report("sql value_int") { sum_int }

x.report("sql value_big_int") { sum_big_int }

x.report("sql value_real") { sum_real }

x.report("sql value_txt") { sum_txt }

x.compare!

end

The result

SUM error = 0.0, text = 68254.85245740146

SUM error = 1.2322943643084475e-13, real = 68254.85245739305

SUM error = 8.360059791236454e-10, bint = 68254.85240034

SUM error = 0.00014105015328355765, int = 68245.2251

Warming up --------------------------------------

sql value_int 1.000 i/100ms

sql value_big_int 1.000 i/100ms

sql value_real 1.000 i/100ms

sql value_txt 1.000 i/100ms

Calculating -------------------------------------

sql value_int 0.573 (± 0.0%) i/s - 6.000

sql value_big_int 0.571 (± 0.0%) i/s - 6.000 in 10.518204s

sql value_real 0.563 (± 0.0%) i/s - 6.000 in 10.667458s

sql value_txt 0.192 (± 0.0%) i/s - 2.000

Comparison:

sql value_int: 0.6 i/s

sql value_big_int: 0.6 i/s - 1.00x slower

sql value_real: 0.6 i/s - 1.02x slower

sql value_txt: 0.2 i/s - 2.98x slowerConclusion

Using integers can improve our calculations but not for much, and the lost precision can be compensated if our values aren’t critical, otherwise using float type it will be just enough. We still can use BigDecimal values, but the cost in the long term run could affect our performance, I don’t recommend use this data type if is not related to something critical in our application. Although we still calculate parabolic trajectories with float data type.